I Participated in Ludum Dare 47 and Made a New Game in a Weekend

Intro

What if I told you that this October, I and thousands of other game developers from all over the world spent a weekend (3rd-6th) making tons of small games from scratch? I’m going to recount here my experience participating in the Ludum Dare Game Jam and how I created my entry: Loopy Boy .

What is a Game Jam, Exactly?

A game jam is an event in which participants create games (usually based on a common theme) from scratch within a set amount of time. These are short events, typically only lasting for about 24-48 hours. Some jams are held in real life while others are held exclusively online. Usually, participants have to follow certain rules decided by the game jam organizers.

Ludum Dare is one of the most established and beloved game jams out there. It’s held twice a year – once in April and once in October. The event has two categories to choose from: Compo and Jam.

Compo’s rules are simple: from the start of the event, participants have 48 hours to create a game completely from scratch. Participants must work on their game alone, with no external help whatsoever, and all the code and other assets (art, music, sound effects, etc.) must be created entirely during that game jam – no reusing of past assets allowed. Jam’s rules are more permissive. For example, you can work with a team, reuse previous code and assets you already have, and the time limit is 72 hours. The two categories are held simultaneously.

The theme is announced at the start of the Ludum Dare, but following it isn’t a requirement to participate. After the time is up, participants have one extra hour to submit their game for everybody to play and rate. Of course, if you finish before the time is up, you can still submit your game right away.

I had participated in the Jam category before with some friends of mine and we had a bunch of fun, but this year, I chose to participate in the Compo category.

Even if the event is held completely online, services like Twitter, Itch.io , and the Ludum Dare website itself help to give a sense of community. Seeing other game developers’ posts creates a mix of excitement and eagerness to work on your own game that’s hard to describe. It really makes you want to stop procrastinating and start working instead, because time is precious and everybody else is working hard to meet the deadline.

Participating in a game jam may seem similar to running a sprint, but for me at least, it’s more like a marathon. You have to go steady and avoid burning out quickly. Creating a game (even a small one) within 48 hours is no joke – you need to pace yourself and take breaks to avoid putting needless strain on your body and mind.

First Day

The night before, I set my alarm so I would wake up just in time for the Compo theme to be announced, which was at 7am local time. The Ludum Dare game jam also started at 7am in my time zone. So, when I woke up, I immediately checked the theme:

“Stuck in a loop”.

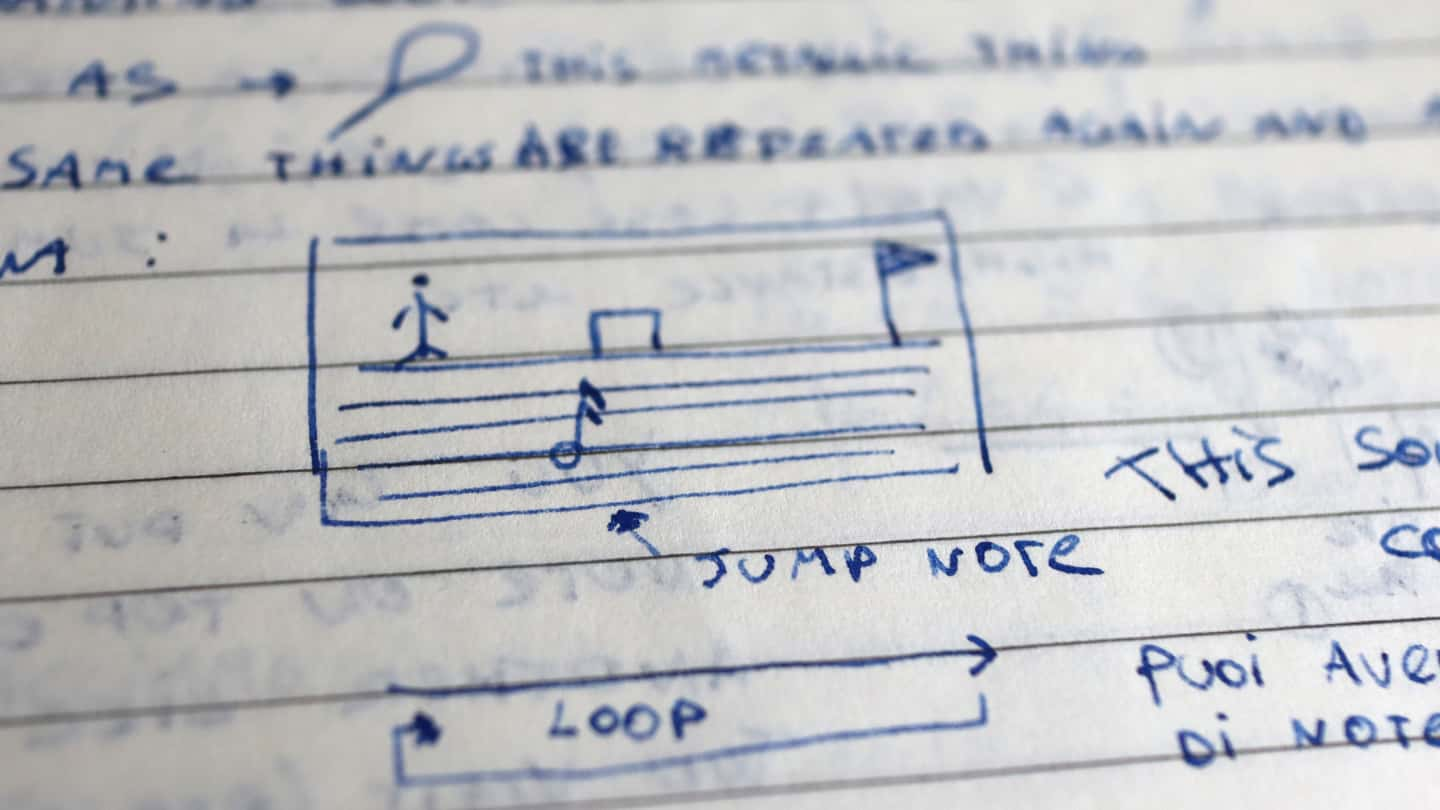

I immediately started scribbling down ideas in my notepad.

My mind was completely blank at first. Stuck in a loop. You’re stuck… in a loop?

I totally didn’t want to go with the old and tired time loop video game concept, so I tried thinking outside the box. What if you’re a musical note stuck in a loop? Or maybe a person stuck in the work, sleep, repeat loop? What about a programming-themed game where you’re stuck in a computer program loop and you must write the code that will help you exit said loop? This idea was kinda interesting, but I couldn’t see myself coming up with a functioning game within the time limit. Since time is extremely tight, it’s important to be able to come up with game ideas feasible enough to be quickly implemented. I also tried coming up with ideas about being stuck in a physical loop (like those loops made out of string or metal), but couldn’t think of anything interesting.

At this point, I started considering the idea of a musical note stuck in a loop as a possible candidate. What kind of gameplay could I build on a premise like that? What about a platform where the player could indirectly control the movements of their character by laying out notes on a piano roll-like interface, thus creating some sort of musical loop? I liked the idea and immediately started sketching a mock-up on paper.

The interface would be vaguely inspired by a piano roll like the ones used in music creation software. Players would drop special notes on the piano roll, and once the playhead reached a note, it would become active and the player character would execute the corresponding action. Different types of notes would make the player character execute different actions. For instance, if the player character was standing still and the playhead reached a “walk” note, the player would start walking.

That was it. I had my rough idea for the game. I fired up Unity and created a new project.

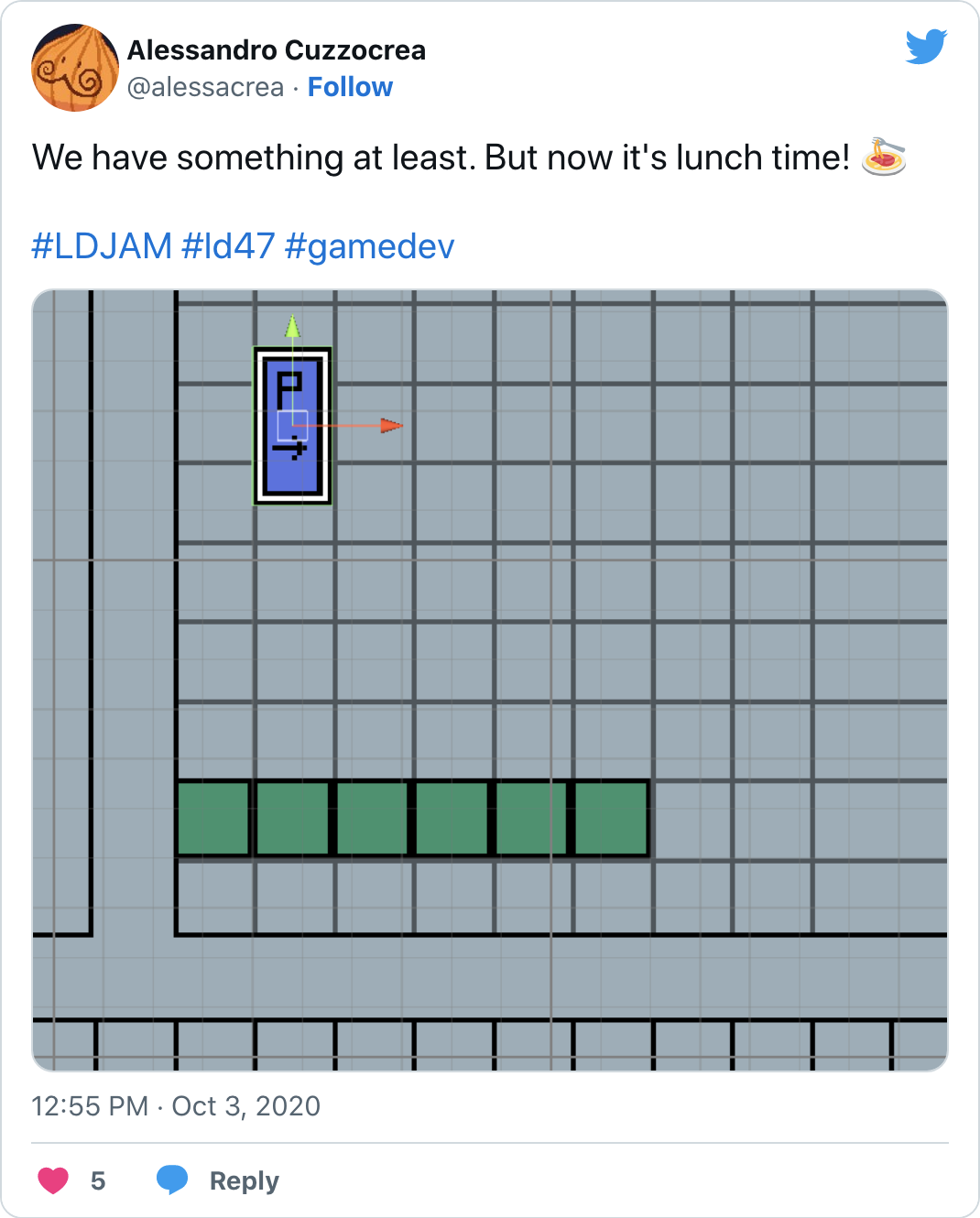

I started by setting up the player character game object with his sprite renderer and colliders. After I finished with that, I wired a simple level made of composable square tiles for quick and easy prototyping. I also coded the main piece of UI that would allow players to interact with the game.

All the graphical assets I was using at this stage were just placeholders. It’s always hard to get the style, proportions, aspect ratio, and scaling right on the first attempt, so it’s better to experiment with placeholders first.

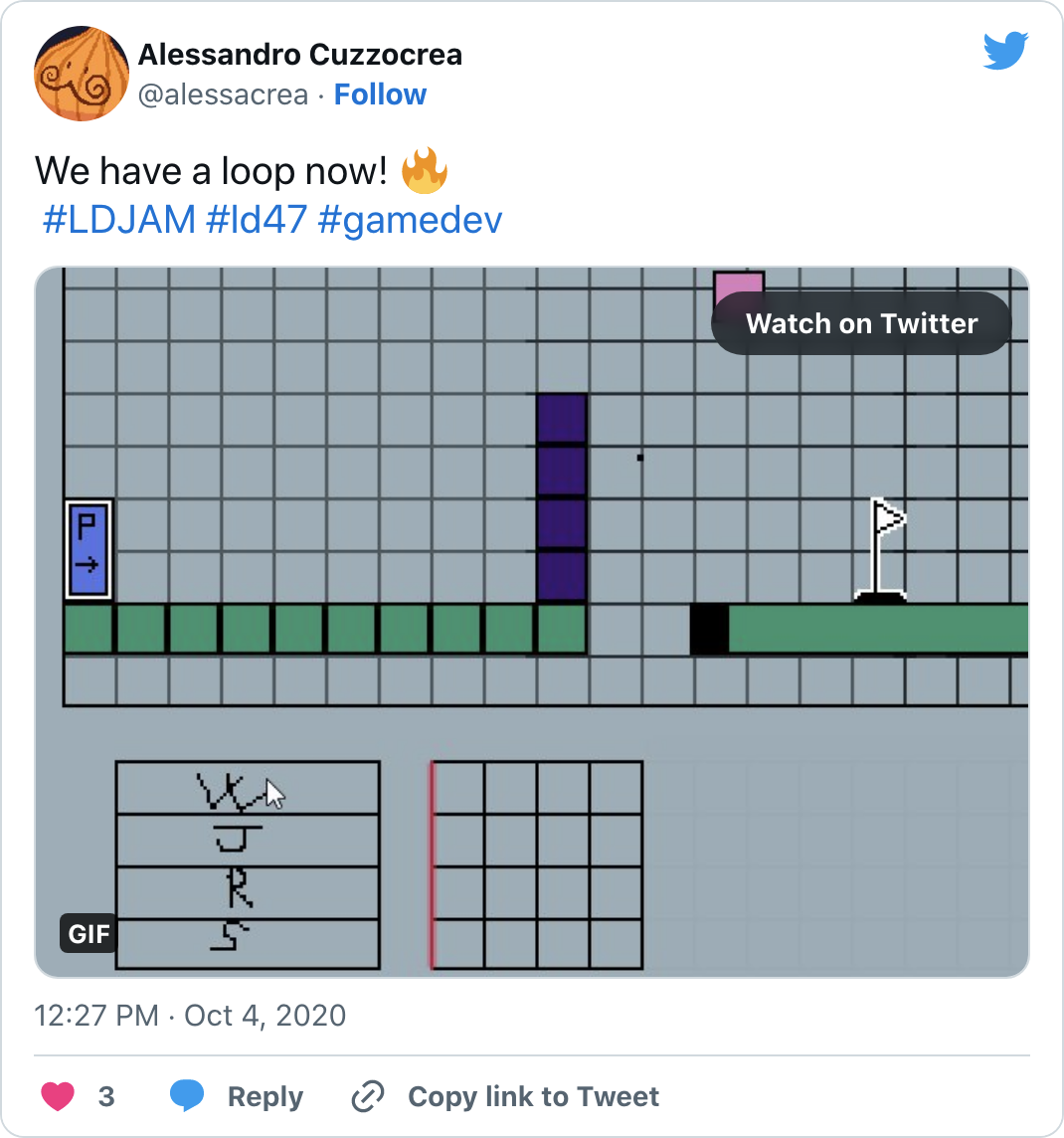

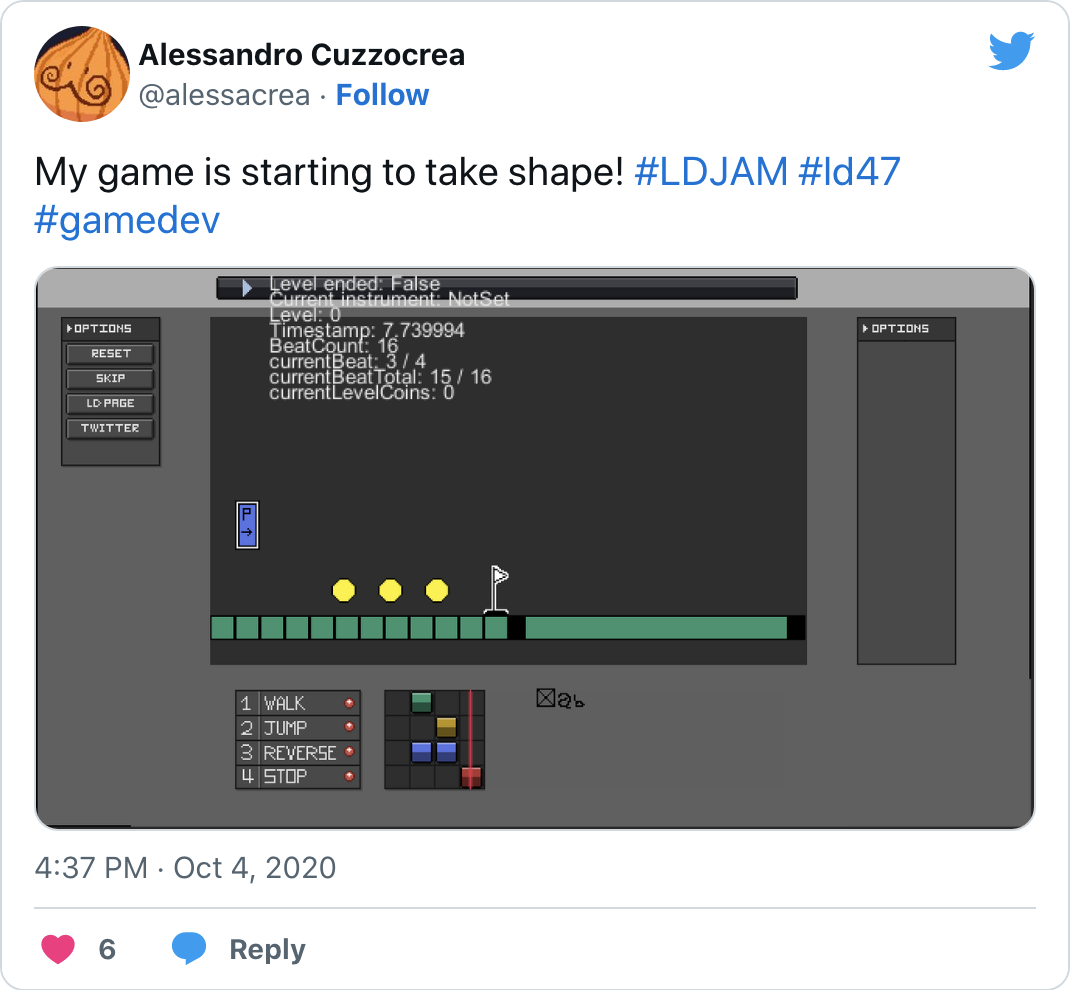

I had put together a prototype by early afternoon. After I finished making some tweaks to the prototype, I decided it was time to go on and implement the full game loop. And just after midnight, the core game loop was complete! Now the piano roll worked as intended and the four basic “notes” were implemented. The player could also reach the goal and collect coins. I gave myself a pat on the back and went straight to sleep.

Second Day

Now that the core gameplay was in place, next up on my to-do list was drawing the graphics and building all the remaining levels (at this point, I’d only done a couple of test levels).

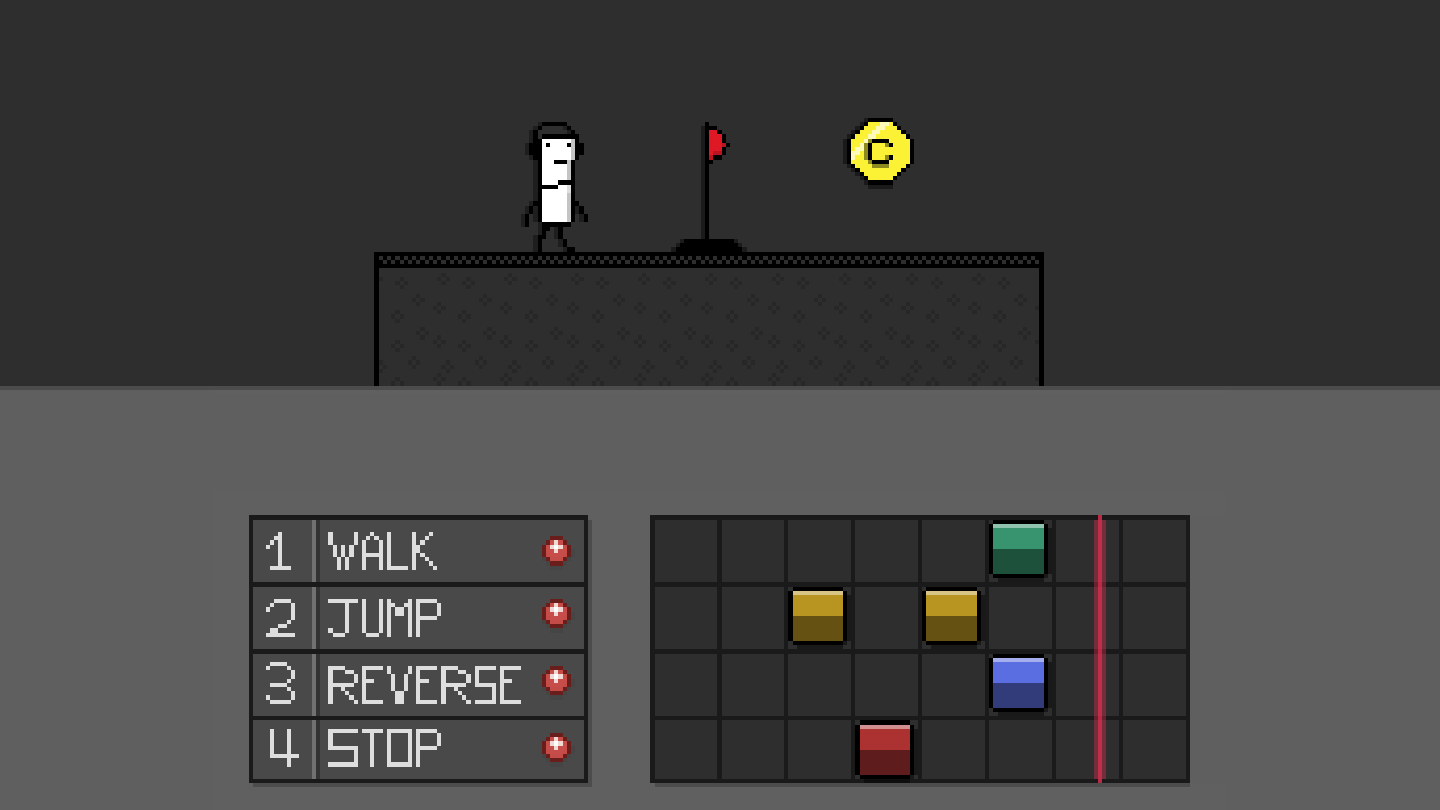

I fired up Aseprite and started working on the game UI. I only had one day left at this point, so I opted for simplistic graphics with minimal animations. Since the player would control the character entirely via clicking the game UI, it made sense to me to concentrate on the UI first.

Pixel art is a ton of fun to work with, albeit time-consuming. When working with pixel art, every pixel counts. It may take some trial and error, especially with lower resolution pixel art, since the placement, color, and contrast of every single pixel is important to produce something that reads well. Anyway, after a couple of hours, I finally had something:

I had so much fun drawing the UI that I just kept working on it, and before I knew it, it was already late afternoon. At 4:37pm, the UI was only half-done and I had yet to start working on the player character sprite.

For the character sprite, I opted for a boxy white character with black outlines and a simple two-frame animation. Because the background was going to be dark gray (like most digital audio workstation programs), I thought that having a high contrast between the white sprite and the dark background would help the player understand what was happening on screen at a glance.

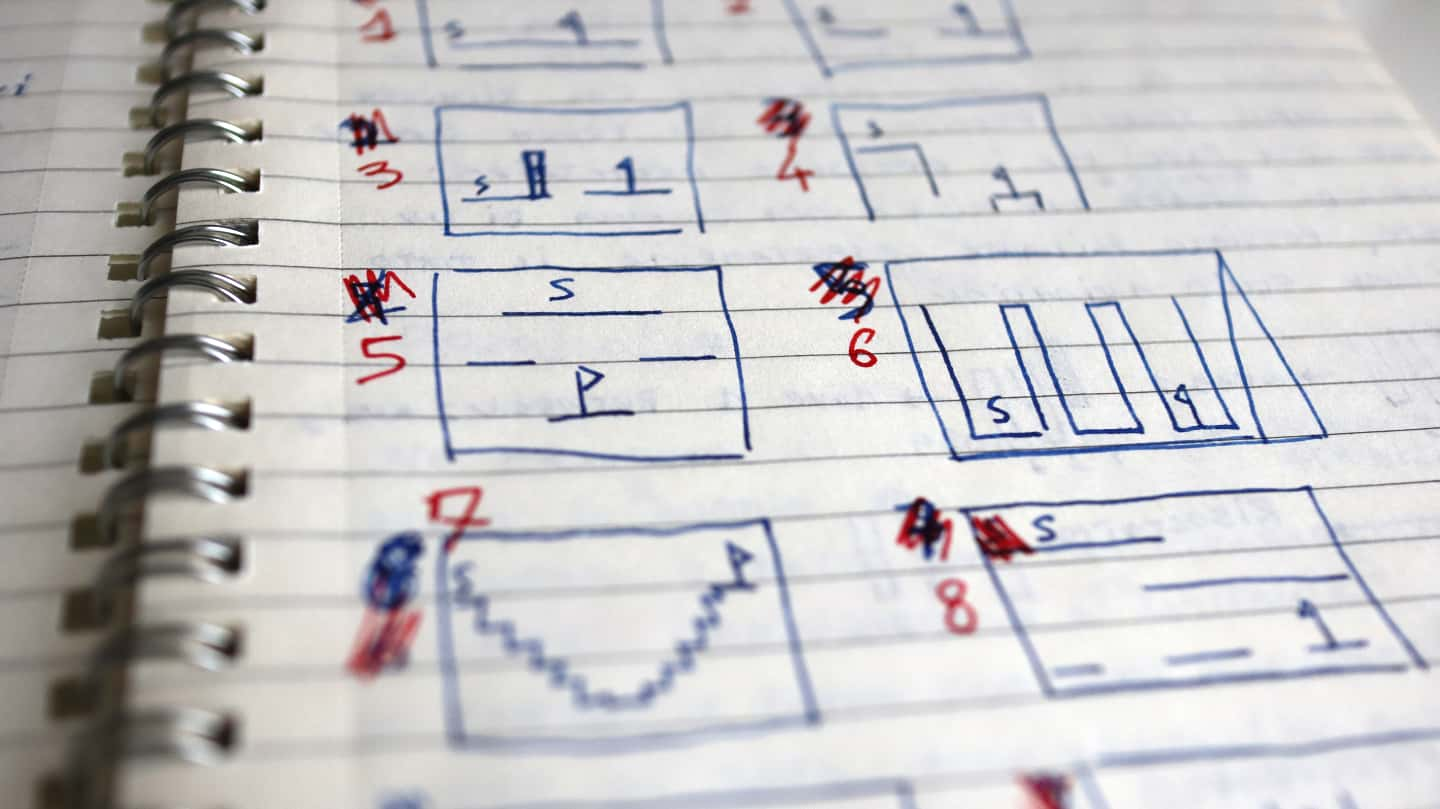

It was getting pretty late and I still had to start working on levels and sounds. At this point, I was getting pretty tired and needed an extended break away from my PC, so I took my notebook and started sketching some levels.

I quickly realized that it was too late to create fully realized levels, each one with a unique gimmick or gameplay mechanic. So, I sketched out some shapes and tried to make levels out of them by basically trying to place coins and goals in interesting ways.

Back at my PC, I immediately realized that I still needed to create the tileset graphics for the levels. At this point, I was still using placeholder tiles. After I made the tiles, it was time to actually build the levels. Every level was going to be stored in its own prefab so it could be easily replaced with the next one when the player reached their goal. Tiles had to be placed by hand, causing implementing all levels to take way more time than I initially anticipated. I could have used Unity’s Tilemap System to simplify the process, but I wasn’t familiar with it and didn’t have the luxury of spending time to learn during the game jam. I’m definitely going to learn how to use it properly before the next Ludum Dare.

I had almost no time left to dedicate to music and sound effects, which was a shame given the game’s musical nature. I quickly generated some sound effects using jsfxr and called it a day.

At this point, the game was almost complete. I was tired, but started testing the game the best I could. I also tested whether the WebGL build was working correctly on Itch. There was a problem with the aspect ratio if the game was played using full screen, but I quickly fixed this by changing some settings on the 2D Pixel Perfect Camera .

By 4:58am, I was finally done with the game. I uploaded the final build on itch.io, submitted my entry to the Ludum Dare site, and went to sleep.

The next morning, I woke up, checked my game’s page, and immediately saw the comments left by other Ludum Dare participants who’d tried my game out for themselves. Seeing how people react to your game is always the best moment of every game jam, at least for me.

The Results

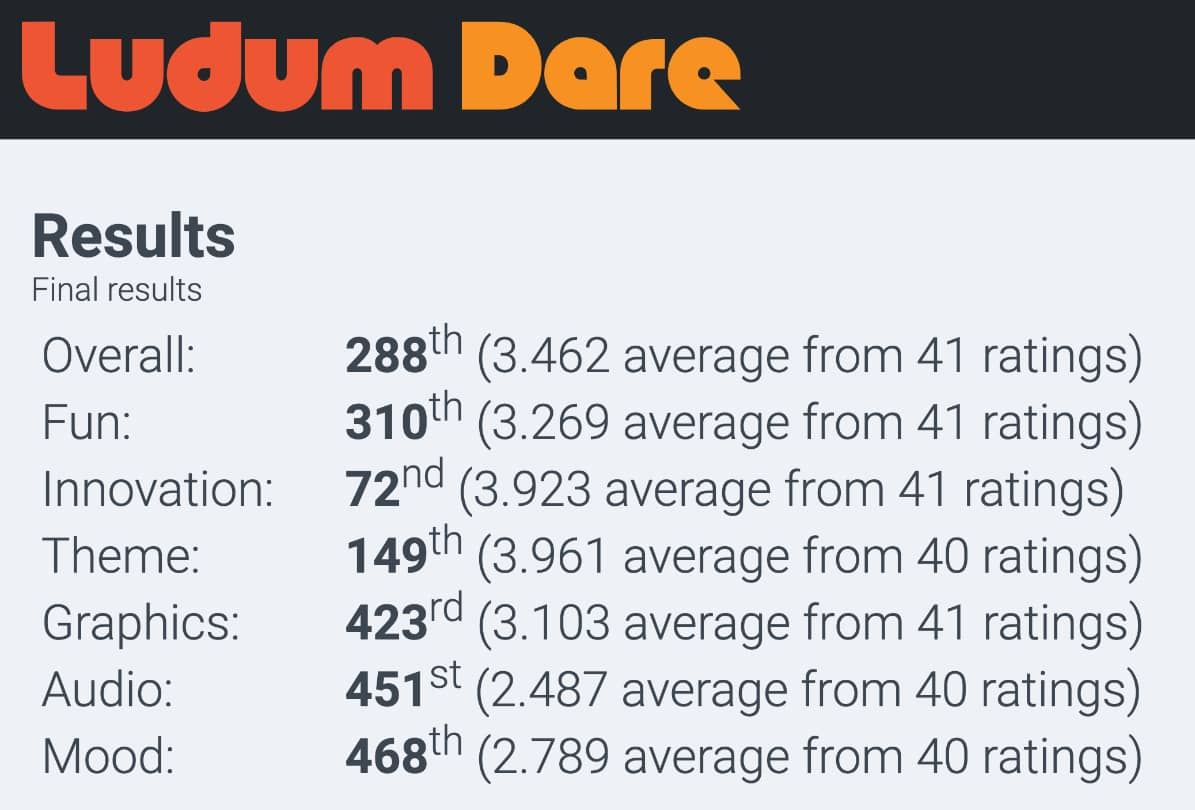

Once the time to submit your game is up, participants are encouraged to play other participants’ games and judge them, leaving 1-5 star ratings in eight categories (overall, fun, innovation, theme, graphics, audio, humor, and mood).

I’d like to address here some of the feedback I got:

Being able to edit the loop in “real-time” is too easy.

This is probably the biggest failure of my game. Initially, there were supposed to be two separate phases: a planning phase and an execution phase. During the execution phase, the player would just see how the planned actions would play out, without the ability to edit the loop in real time. Sadly, when I was developing the first prototype, I quickly realized that this would require extensive design and testing to ensure every level was beatable. There wasn’t time for that, so I ended up combining the two phases into one, resulting in the player being able to change the loop on the fly. This made the game less challenging – now the player could react to whatever the level threw at them by just swapping out notes whenever they felt the need to do so.

I had trouble figuring out some of the moves. A tutorial would have helped.

A tutorial would definitively have helped to better understand how to play the game, since the UI could be pretty confusing. The first level was supposed to be one of those kinds that teaches the player the game mechanics without really being a “tutorial”, but evidently, this wasn’t enough.

A little unintuitive that “move” just means “start moving”.

I noticed this when I was approaching the end of development. This was bad because it clashed with how the other actions worked, ruining the game’s consistency. Unfortunately, it was too late to change it.

You could improve the sound effects, maybe with some variations.

That was absolutely true, and it’s something I need to get better at before the next game jam.

Graphics are gray and dull.

This was also true. I tried to get as close as possible to the UIs of those DAW software tools I used as inspiration. In hindsight, I should have added a subtle tint of blue or something to make the UI look more lively.

Thank you to all the kind participants who took the time to try out my game and give me constructive feedback!

I ended up placing 72nd in the innovation category!

That was pretty cool.

Back to Unity

I used this opportunity to revisit Unity and reconsolidate my knowledge. Unity has changed a lot in the 5 years I haven’t touched it.

Using prefabs is now more convenient thanks to the newly revamped workflow supporting “real” nested prefabs. I love how you can now just edit the prefab in its own separate “environment”. Before, you had to manually drag and drop the prefab in the scene, make your modifications, click apply, and then delete it from the scene. This was necessary every time you wanted to make some changes to a prefab. The old workflow was time-consuming and error-prone.

I’m also really pleased with the increased performance on mobile. Creating (or appending) the Xcode project for your game feels way faster than before. I don’t know if it’s just that we now have faster hardware, but I remember it being so slow back in the day. The WebGL build likewise feels more lightweight and faster to load.

Closing thoughts

Finishing a game is so motivating and inspiring. Participating in game jams is a great way to practice creating games from start to finish (albeit on a smaller scale).

Action-based puzzle games are more difficult to design and test compared to non-action turn-based ones.

I should have spent less time polishing the UI. Other aspects of the game like level design, music, and sounds suffered because there was no time left after I was done with it.

Next time, I will focus on only one major game mechanic. Making a game with fewer but stronger mechanics makes for a more cohesive game experience for the player.

Time is a limited resource that must be managed carefully. Although you can’t plan your game and prepare assets before the game jam starts, be sure to learn and review how to use any tool that may come in handy for the jam to avoid wasting time looking up stuff online.

Make your game playable in a web browser. I saw way too many entries with barely any votes/comments because they couldn’t be played in a browser. Not many people are willing to download and run executables from unknown developers.

Your entry’s Ludum Dare page is important. Set aside some time to create a compelling page with a nice header picture and a short but helpful explanation of your game.

Code quality was, as expected from a game made within 48 hours, atrocious. But the interesting thing was how I felt comfortable working with a codebase with such a large technical debt. I guess the lesson here is that as long as you can fit the entire codebase in your head, it’s going to be fine no matter how lousy it may be. And that’s why it’s important to keep your code clean and easy to understand when working in a team (or for your future self who will inevitably forget most of the code in a couple of days).

It’s easy to forget stuff when you’re in a rush. Try keeping track of things with to-do lists or Kanban boards (e.g. Trello ).

I kept track of time during the jam using Toggl . Here’s the data grouped by category:

| Category | Duration | % |

|---|---|---|

| Coding | 9:05:51 | 33.46 |

| UI | 5:32:26 | 20.38 |

| Sprites | 2:42:51 | 9.98 |

| Level Design | 2:23:09 | 8.77 |

| Game Design | 2:15:43 | 8.32 |

| Brainstorming | 1:55:18 | 7.07 |

| Testing | 0:58:48 | 3.60 |

| Project Setup | 0:50:32 | 3.10 |

| Audio | 0:33:22 | 2.05 |

| Animations | 0:29:24 | 1.80 |

| Release | 0:24:03 | 1.47 |

| 27:11:27 | 100.00 |

Links

Related Articles

Ludum Dare 50: Delay the Inevitable

Ludum Dare 50: Delay the Inevitable Push Golf and the Unreal Engine 5 Petit Contest: Creating the Game (Part 2)

Push Golf and the Unreal Engine 5 Petit Contest: Creating the Game (Part 2) Push Golf and the Unreal Engine 5 Petit Contest: From Nostalgia to a Game Jam (Part 1)

Push Golf and the Unreal Engine 5 Petit Contest: From Nostalgia to a Game Jam (Part 1) Starting out with Godot

Starting out with Godot Tearful Heart Retrospective

Tearful Heart Retrospective